Fawcett (2010: 213-4, 213n-4n):

The main characteristic of an element is that it is defined functionally, rather than positionally. This should surely be a founding principle of a functional approach to syntax — and yet the tradition of using positional labels still lingers on in many functional grammars.¹⁷

¹⁷ For example, terms such as 'pre-deictic' and 'pre-numerative' (as found in Halliday 1994:195-6) are simply positional labels. Rather similarly, the terms 'premodifier' and 'postmodifier' (Halliday 1994:194-5), signal a positional meaning more strongly than they signal a functional meaning. This is because, at Halliday's primary level of delicacy in the analysis of a nominal group, the term 'modifier' means little more than 'anything other than the head'. So these terms give virtually no information about the element's function.

However, I must admit to retaining one traditional 'positional' label in the Cardiff Grammar, i.e., 'preposition'. As said in Section 10.2.6, I would have preferred an explicitly functional label, but terms such as 'relator' are not specific enough, and we retain the traditional term "preposition" both because there is a lack of a clear alternative and because it is so strongly established. We define it as functioning to express a 'minor relationship with a thing'. Note that in the description of English one item that actually occurs 'postpositionally' is included as a 'preposition' — i.e ago, as in five years ago.

Blogger Comments:

[1] This is misleading (and hypocritical) because, contrary to the implication, Fawcett's own approach to functional syntax includes elements that are defined positionally. As can be seen from the previous post, Appendix B (p304), lists:

- 'Starter' and 'Ender' as elements of the clause,

- 'finisher' as an element of the quality group,

- 'quantity finisher' as an element of the quantity group,

- 'starter' and 'ender' as elements found in all groups, and

- 'Opening Quotation mark' and 'Closing Quotation mark' as elements of a text.

[2] This is misleading, because it is untrue. The terms 'pre-Deictic' and 'pre-Numerative' are not "simply positional labels", since they identify the functions 'Deictic' and 'Numerative' respectively. However, the function 'pre-Deictic' — unlike 'post-Deictic' — is not an element in Halliday's model, and the 'pre-Numerative' was later termed 'extended Numerative' (Halliday & Matthiessen 2004: 333).

[3] This is misleading, because it is untrue. The term 'pre-Modifier' and 'post-Modifier' do not signal positional meaning more strongly than functional meaning, since they identify the function 'Modifier' and, through prefixes, additionally provide the location of the modification relative to the Head.

[4] This misrepresents Halliday. To be clear, in SFL Theory, delicacy is a dimension of paradigmatic system, not syntagmatic structure.

[5] To be clear, here Fawcett misleads through his ignorance of the notion of univariate structure: 'an iteration of the same functional relationship' (Halliday & Matthiessen 2014: 390, 451).

[6] As can be seen from the four preceding points, this is the direct opposite of what is actually true.

[7] To be clear, 'preposition', as a class of word, is a unit of form, so renaming it with a function label would be theoretically inconsistent. In SFL Theory, a preposition functions as a minor Process/Predicator of a prepositional phrase.

[8] To be clear, in SFL Theory, the experiential function of a preposition, minor Process, relates to the function of a nominal group, Range, in a prepositional phrase, whereas Thing is an experiential function of a word in a nominal group.

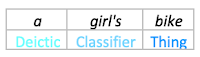

[9] To be clear, the word ago is an adverb, not a preposition, and five years ago is a nominal group, not a prepositional phrase: