We shall start by noting that there is a little evidence that 'rank' may have diminished in importance a little in Halliday's theory too. In Chapter 5 we saw that 'rank' is presented in Halliday's "Systemic theory" (1993) as a type of 'constituency', but with no hint of 'total accountability at all ranks'. Then in Chapter 6 we saw that, although it is present in the background in IFG, the concept of 'rank' is only actually used in the context of 'rank shift' in the descriptive part of the book. It is reasonable to ask, therefore, how far the concept of the 'rank scale' is still the foundation of Halliday's theory of syntax today, as it was in "Categories".

The answer is that it is hard to be sure. Let us look at what Halliday says in the one place in his recent writings when he gives time to the question of the 'rank scale', i.e., the last section of Chapter 1 of IFG. By p. 12 he has introduced the reader to the general concept of 'constituency', and he is illustrating the proposal that it can be "strengthened" by adding to it the concept of the 'rank scale'. As he then says, the "guiding principle [of the concept of the 'rank scale'] is that of exhaustiveness at each rank". (This is also known as the "total accountability at all ranks" principle.) This means, for example, that in Most people love chocolate the word chocolate is treated as the head of a nominal group that fills the Complement of a clause — rather than simply functioning as a direct element of the clause. Most linguists, of course, including those who are not adherents of the 'rank scale' concept, would agree with this analysis (or some broadly equivalent one).

Blogger Comments:

[1] This is misleading, because it is untrue, since, inter alia, the rank scale provides the entry conditions to different lexicogrammatical systems. For example, the rank of clause is the entry condition for the systems of THEME, MOOD and TRANSITIVITY.

[2] This misleading. On the one hand, the inclusion of the rank scale in Halliday (1993) is evidence of its importance in SFL Theory. On the other hand, logically, the lack of discussion of 'total accountability at all ranks' does not imply that rank has "diminished in importance", and the lack of discussion is explained by the fact that Halliday (1993) is a very brief outline of SFL Theory in an encyclopædia for a general — not specialised — readership.

[3] This is misleading because it is not true. As previously observed, IFG (Halliday 1994) is largely organised on the basis of rank, beginning with the clause, then group/phrase, then complexes at clause rank, then complexes at group/phrase rank.

[4] This is misleading on several fronts. Firstly, it is not reasonable to ask this question; see [1], [2] and [3] above. Secondly, the rank scale of forms is not the foundation of either of Halliday's functional theories, but one of their many dimensions. Thirdly, as previously demonstrated, Halliday's theory is not a theory of syntax, as Halliday (1994: xiv) makes perfectly clear. Fourthly, it is not hard to be sure on this matter; see see [1], [2] and [3] above.

[5] This is misleading, because it is not true. Halliday (1994: 12) does not propose that the concept of constituency can be "strengthened" by adding to it the concept of a rank scale. Instead, Halliday (1994: 20-4) illustrates that the rank scale is one of two ways of modelling constituency: that of minimal bracketing or ranked constituent analysis, as opposed to maximal bracketing or immediate constituent analysis.

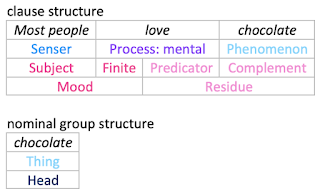

[6] This is potentially misleading. In SFL Theory, in this instance, the word is not "treated" as the Head of a nominal group; the word realises the Head element of nominal group structure. The word (form) and its function at group rank are different levels of symbolic abstraction.

By the same token, the nominal group does not "fill" the Complement of the clause. The nominal group realises the Complement element of interpersonal clause structure. The group (form) and its function at clause rank are different levels of symbolic abstraction.

Moreover, it will be seen in future posts that the wording "functioning as a direct element" is a source of Fawcett's confusion. To be clear, in this instance, the nominal group chocolate serves as the Complement/Phenomenon of the clause, and the word chocolate serves as the Head/Thing of that nominal group.

No comments:

Post a Comment