In my view, then, it is unhelpful to have 'primary' and 'secondary' structures in the representation of a clause. Firstly, it implies that elements form a 'multiple element', when the evidence from the syntactic distribution of the elements themselves shows that they do not. Secondly, they risk introducing misunderstandings about the number of 'strands of meaning' in a clause.However, while the concept of 'more delicate structure' has no place in a modern theory of SF syntax, I have to admit that the Cardiff Grammar's description of English still contains a few historical remnants of the concept. One is found in the convention that the term "modifier" is used as the second part of the names of many different elements in the nominal group, e.g., the "affective modifier", the "epithet modifier", and so on. And the same goes for Adjuncts and, to a lesser extent, determiners in the nominal group and Auxiliaries in the clause. (See Appendix B for examples.) Moreover, at the introductory level of text description we simply use "m" for all the different types of 'modifier', "X" for the different types of 'Auxiliary Verb', and so on.

Blogger Comments:

[1] As previously explained, the architecture of SFL Theory does not include the notion of primary and secondary structures distinguished on the basis of delicacy. This was a feature of Halliday's superseded theory, Scale & Category Grammar (1961) — the theory on which Fawcett's "modern theory of SF Theory" is based.

[2] This is misleading and confused. It is not that elements "form a multiple element", but that one element such as Theme, Mood or Residue can itself be composed of elements.

[3] This is misleading. On the one hand, Fawcett does not produce the evidence that he claims exists, while on the other hand, in a functional grammar, the criterion for structural elements is their function (the view 'from above'), not their syntactic distribution (the view 'from below').

[4] This is misleading, because it is untrue. The number of strands of meaning in the clause is unambiguously three, because they are metafunctionally defined. The average academic can distinguish between the theoretical principle and the number of rows in a representation of structure.

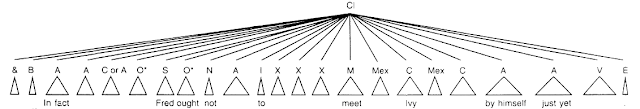

[5] This is misleading. To be clear, presenting a single line of structural analysis with multiple elements with the same label, as illustrated in Appendix B (pp305-6), does not exemplify Halliday's (1961) double-layered structures of primary and secondary delicacy:

No comments:

Post a Comment