Fawcett (2010: 263):

There are three types of recursive relationship in English: co-ordination, embedding and reiteration. Reiteration is much less central to the grammar of English than the other two, and it is used more in other languages. But do 'recursive structures' in fact occur in language? Strictly speaking, they do not.

Recursion occurs when a choice in the system network leads to a realisation rule which specifies a re-entry to the system network and the choice of the same feature again. What we find at the level of syntax is two types of the 'repetition' of a class of unit and, in reiteration, the repetition of an item (as in He's very very happy.). All three of these are cases of the realisation at the level of form of recursively selecting the same feature in the system networks. The effect of choosing such a feature is to generate a unit alongside an existing unit (this being is co-ordination) or inside another unit (this being second embedding [sic]. In the strict sense of embedding, a unit fills an element of the same class (most frequently a clause filling an element of a clause, as illustrated in Appendix B). In co-ordination the two or more co-ordinated units are typically of the same class — but not necessarily, as we will see in the next section. (We shall recognise a looser sense of 'embedding' in Section 11.8.3.)

It is the relationship of filling that makes possible the first two types of recursion, and the relationship of exponence that enables reiteration to occur.

Blogger Comments:

[1] To be clear, these claims are theory-dependent and represent Fawcett's position on the phenomena.

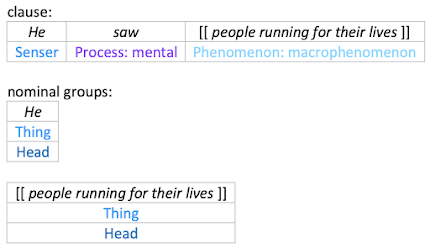

[2] In SFL Theory, RECURSION is a system that specifies complexing at all ranks. Halliday & Matthiessen (2014: 438) provide a clause rank example:

Importantly, recursion does not necessitate "the choice of the same feature again".

[3] To be clear, from the perspective of SFL Theory, these two types of repetition are both cases of complexing: the first at ranks above the word, the second at word rank.

[4] To be clear, SFL Theory makes a very important distinction between taxis ("co-ordination") and rankshift (embedding). This distinguishes, for example, non-defining relative clauses (taxis) from defining relative clauses (rankshift), and projected ideas (taxis) from pre-projected facts (rankshift).

[5] To be clear, contrary to this strict sense of embedding, Appendix B (p306) presents both a preposition group in Kew and a clause we've seen as elements (qualifiers) of a nominal group.

[6] To be clear, in this later discussion, it is the nominal group of a preposition group that is said to be embedded in a nominal group, thereby allowing him to overlook the prepositional group as an embedded unit. Fawcett (p264-5):

The second type of recursion is embedding. This occurs when a unit fills an element of the same class of unit — and also, in a looser sense, when a unit of the same class occurs above it in the tree structure. So we shall not say that we have a case of embedding in on the table, where the nominal group the table fills the completive of the prepositional group on the table … . However, if the table occurred in the box on the table, this is embedding in a looser sense of the term, because the nominal group the table fills the completive of the prepositional group on the table, and this in turn fills the qualifier of the higher nominal group the box on the table.

And, in an even looser use of the term, one could refer to any case in which a unit appears lower in the tree than the second layer as 'embedding'. Here, however, I shall normally use the term "embedding" in the sense of the occurrence (direct or indirect) of a class of unit within the same class of unit.

[7] To be clear, from the perspective of SFL Theory, the "first two types of recursion", co-ordination and embedding, correspond to taxis and rankshift. However, clause complexes (taxis) do not realise ("fill") and element of a higher structure, though rankshifted units do. Fawcett's third type of recursion, reiteration, corresponds to a paratactic elaborating word complex realising ("expounding") an element of group structure.