Fawcett (2010: 210):

Figure 12 shows two of the main types of 'congruent' and 'incongruent' relationship, as they affect clauses and nominal groups. In the terminology of the Cardiff Grammar, the language expresses 'higher' beliefs (these being represented in logical form). Then, within language, forms realise meanings. Thus, if an event in the belief system is mapped onto a situation in the semantics (which will in turn be mapped onto a clause in the syntax at the level of form), then the relationship between the 'event' and the 'clause' is said to be congruent — a term introduced by Halliday (1970:149). However, an event can be incongruently realised as a nominal group, i.e., when 'nominalisation' takes place, as in his entering the room at that moment. And an object can be incongruently realised as a clause, as in what you gave me for my birthday.

Blogger Comments:

[1] To be clear, in Fawcett's model of grammatical metaphor, clauses and nominal groups are not affected by the distinction between congruent and incongruent relationships, because in either case, a clause realises a situation and a nominal group realises a thing.

[2] As previously explained, Fawcett's 'belief system' outside language is inconsistent with the epistemological assumptions of SFL Theory (Halliday & Matthiessen 1999: 3). In SFL Theory, beliefs are ideas, which are mental projections of linguistic meaning.

[3] As explained in the previous post, Fawcett nowhere discusses his model of logical form, and his location of it outside language is inconsistent with its usage in linguistics, philosophy and mathematics.

[4] To be clear, in SFL Theory, grammatical forms are interpreted in terms of the functions they serve, and their function is to realise meaning. In the absence of grammatical metaphor, the function of grammatical forms and semantics agree (are congruent). It is because Fawcett's model exports grammatical functions to his level of meaning that he is required to invent a yet higher level, outside language, in an attempt to account for grammatical metaphor.

[5] To be clear, the in/congruent relation obtains only between adjacent levels of symbolic abstraction (strata) and only between strata that are related non-arbitrarily ('naturally'), that is: between semantics and lexicogrammar.

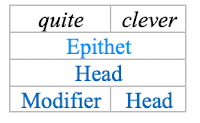

[6] To be clear, the wording what you gave me for my birthday is not a clause, but a nominal group with an embedded clause as Qualifier: