Fawcett (2010: 165):

8.4 The 'relationships' of "Some proposals"

The first difference is that "Some proposals" recognises many more 'relationships' than the three 'scales' in "Categories". There are ten of them.

One of its major innovations is to split Halliday's 'scale' of 'exponence' into three: componence, filling and exponence proper. To cite Butler's excellent summary of these concepts:

Componence is the relation between a unit and the elements of structure of which it is composed. For example, a clause may be composed of the elements S, P, C and A. Each of these elements of structure may be (but need not be) filled by groups. In the specification of a syntactic structure, componence and filling alternate until, at the bottom of the structural tree, the smallest elements of structure are not filled by other units. It is at this point that we need the concept of exponence, as used by Fawcett: the lowest elements of structure are expounded by items', which are [...] more or less equivalent to 'words' and 'morphemes' in Halliday's model. (Butler 1985:95)

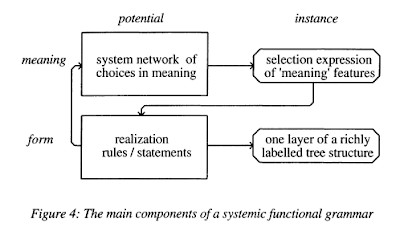

These three concepts, which today still form the basis of the Cardiff Grammar's model of syntax, are clearly exemplified in the top half of Figure 10. These concepts are necessary, in one form or another, in any adequate systemic functional model of syntax, and they will be illustrated, discussed and compared with their antecedents in the relevant sections of Chapter 11.

Blogger Comments:

[1] As previously noted, Fawcett's "Some proposals" (1974) was oriented to Halliday's first theory, Scale and Category Grammar, after it had been superseded by Halliday's second theory, Systemic Functional Grammar.

[2] To be clear, in Halliday's first theory, the term 'exponence' covered what were to become two distinct relations in his second theory: realisation and instantiation. On the one hand, exponence corresponds to the relation between an element of function structure and the class of unit that realises it. Halliday (2002 [1961]: 54, 57):

The exponent of the element S in primary clause structure is the primary class nominal of the unit group. …

The fact that by moving from structure to class, which is (or can be) a move on the exponence scale, one also moves one step down the rank scale, is due to the specific relation between the categories of class and structure, and not to any inherent interdetermination between exponence and rank.

On the other hand, exponence corresponds to the instantiation relation between theory and data. Halliday (2002 [1961]: 57):

Exponence is the scale which relates the categories of the theory, which are categories of the highest degree of abstraction, to the data.

[3] To be clear, 'componence' is the relation of composition, a type of extension. In SFL Theory, composition is modelled as a

rank scale of forms, and is distinct from the

function structures of the units on the rank scale.

[4] To be clear, one the one hand, Fawcett's 'filling' corresponds to the relation between an element of clause structure and the group that

realises it, but treats these two distinct levels of symbolic abstraction, function and form as if both were at the same level. On the other hand, 'filling' suggests an active process, rather than an inert relation, and if this were a model of human language, rather than an algorithm for text generation, the process would be (an aspect of) instantiation.

[5] To be clear, Fawcett's 'exponence' corresponds to the relation between an element of group structure and the word (and morphemes) that realise it. That is, it is a different term for the same relation as 'filling': realisation.

[6] This is misleading, because it is untrue. As can be seen below, while Figure 10 does exemplify Fawcett's notion of componence, a

form (clause)

composed of

functions, it does not exemplify the filling of clause functions by groups or the exponence of groups by words and morphemes. (The 'text' line is the data being analysed, not an analysis of the data at group or word level.)